Treesha Lall, Consultant at Avalon Consulting, contributed his perspective on “Securing Energy Justice with Integration of Renewables and Battery Storage” submitted as part of Cordence Worldwide’s “The Insight Initiative,” a global blog and position paper competition for young consultants in the YPN network.

She examines how renewable energy and battery storage systems can address deep-rooted energy inequities by improving access, reliability, and affordability for underserved communities. Treesha highlights how BESS can democratize energy systems, strengthen rural electrification, and ensure fair distribution of benefits positioning it as a critical tool for achieving true energy justice in developing regions.

1. Introduction

Over 1.37 million people live in Koraput, a district in Odisha, India. In 2011, the Census of India showed only 40% of all households with electricity access in the district . A survey in 2019 recorded a significant improvement – 90% of the total population were electrified. Even then, power outages were significant, averaging only 8-10 hours per day in the mainly rural parts of the district. For these households (83% of Koraput’s total population and economically disadvantaged) energy costs (of electricity but also fuel for cooking) could represent 10-12% of their annual household income .

Electrification and energy are often hailed as a pillar of advancement for the human civilisation. At its core, energy today can be defined as the economic activity of generating power through fossil fuels (coal, petroleum etc.) and renewables (solar, wind and hydropower) and distributing it. A necessity that transcends geopolitical boundaries, energy access and reach can sometimes be the lynchpin for national prosperity. While, therefore, issues of electricity extraction, generation and control are critical, it is equally important to probe the notion of energy justice.

The story of Koraput is one like many towns and villages across the colloquial Global South. Energy injustice manifests in several ways, for instance, energy poverty refers to the continued lack of minimal and basic access to energy – for transportation, electricity and cooking. Energy insecurity refers to the unsafe and uncertain access to electricity. Finally, energy burden refers to bearing the financial strain of energy access. All three factors disproportionately hit economically disadvantaged and socially marginalised communities.

Over the years, developing nations specially made significant strides in improving energy equity. Concerted policy efforts first targeted comprehensive household grid connections. In 2005, the Rajiv Gandhi Grameen Yojana in India electrified 400,000 rural households across the nation .

Between 1994 and 2004, South Africa expanded energy access from 36% of the population to 66%, by strengthening public funding and government bodies to regulate the system. Mexico, Chile and Brazil invested significantly in public-private partnerships to install a cumulative 31.5 GW, investing USD 21 billion between 2002 and 2012 . As supply chains strengthened and heavy industries were domesticised, energy prices fell significantly at the turn of the new century.

2. Energy Justice and Renewable Energy

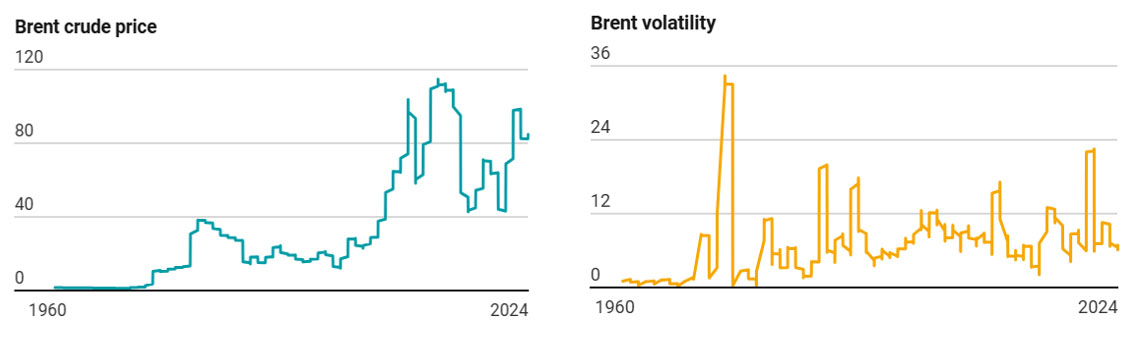

Despite these initiatives, energy was still heavily reliant on fossil fuel (focusing on LPG, natural gas and coal powered energy). Connected to prices of crude oil and petroleum, therefore, energy prices were volatile and spiked frequently between 2010-2020 (Figures 1 and 2). Power generation plants were also located such that the externalities of air, land and water pollution disproportionately affected marginalised communities.

Figures 1 and 2 : Crude price and Crude Price Volatility 1960-2024

The transition to renewable energy has, in part, alleviated many of the energy insecurity and burden issues as they traditionally manifested.

Developing countries made many strides in renewable energy. Africa on a whole doubled its renewables capacity between 2012 and 2020 to 596 GW, with solar energy being the fastest growing sector (recording 60% YoY growth in off-grid instalments between 2009 and 2019). Brazil leads renewables investments in Latin America with the entire region having amassed over 15 billion in annual renewables investment . In Asia, Japan and South Korea are making significant strides in green hydrogen. India nearly tripled its renewable energy capacity between 2014 and 2025. China has been doubling its solar and wind capacity every 2 years on average over the last 2 decades.

However, as the world transitioned to solar, wind and hydro power, new challenges in energy equity and justice. As countries favour development of energy efficiency, much of the work done in energy equity reverses . For many countries, renewable energy transition and energy reach have become goals at opposing ends. A case in point is that of Malawi, that installed 300 MW of coal-powered electricity, doubling national supply and protecting the country from an over-reliance on hydropower and susceptibility to outages from droughts. This action contrasted targets set for renewable energy provision for the nation with organisations like the World Bank .

Without the benefit of scale, solar and wind power generation and distribution is expensive to power. Similarly, dependence on wind and sunshine makes availability insecure. Lack of technology adoption makes availability scarce in under-developed regions.

As renewable energy begins powering more products and services – automotives, household and commercial electricity, as well as public offerings of education and healthcare, making renewable energy equitable today is more important than ever.

3. Energy Justice and BESS

Battery storage stores excess electrical energy generated by solar and wind sources as chemical energy. It can act as a store grid-to-grid or from source of generation to grid. It normally uses lithium-ion batteries for storage, but sodium-sulphur and flow-batteries are also being developed.

Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) addresses the problem of energy injustice by contributing to three major pillars – procedural justice, distributional justice and recognitional justice

A. Procedural Justice: Procedural justice refers to the ability of communities to have the power to make decisions about energy access and provision

BESS has the ability to democratise electricity systems unlike ever-before. Reducing distributional costs significantly and mobilising base generation assets, BESS can be offered to residents as an off-grid or local solution. This decentralization makes energy users “prosumers” (producers and managers) of their energy. In Australia, for example, a community battery storage program allows residents to collect data, have a board of representatives and make decisions on use and pricing. These collective ownership models also allow the communities to have a share in the revenue generated.

BESS also ensures data transparency, tracking real-time usage, distribution, emissions and pricing data.

B. Distributional Justice: Distributional justice refers to the ability for individuals to fairly divide benefits and burdens of energy generation and distribution. BESS, with its ability to store energy and access remote grids, is an effective solution under this pillar.

In Africa, for example, BESS are combined with microgrids – small energy systems that operate independently from main electricity grids – to reach remote, rural regions. It also allows these communities to avoid power instability and surges, allowing these regions to avail cost savings and clean, stable supply like their urban, well-off counterparts. As of 2023, there are 3,000+ microgrids a BESS installed in the sub-Saharan region.

C. Recognitional Justice: Recognitional justice refers to acknowledging and respecting the diverse experiences of communities and their historical experiences

By ensuring that the decision-making is decentralized at community levels, BESS can ensure that cultural context is accommodated in provision. For indigenous communities historically marginalised, for example, land rights and local governance structures can be respected.

Recognitional justice can also look like reparations by way of easier access to public services like education and healthcare – uninterrupted power supplies to local schools and hospitals, as well as cost saving.

BESS can reduce the energy burden on vulnerable communities by reducing peak charges, and generation once infrastructure is in place.

4. Conclusion

Significant advances have been made in the proliferation of battery storage systems in developing countries. However, much work is still to be done in making renewable energy equitable world-wide. Ensuring this will need an examination of how BESS can be modelled to country/culture-specific advantages and constraints. It will also be important to consider other solutions that can be paired with BESS to improve energy equity. As the world readies itself for this large-scale energy transition, Technological and policy strides made for equitable distribution today will go a long way tomorrow.

Treesha Lall

Treesha Lall is a strategy consultant with a background in economics. At Avalon, she has been involved in market entry assessment, commercial due diligence and strategic re-positioning studies. She has a keen interest in leveraging conventional consulting methods in the sustainability and development space.

Email : treesha.lall@consultavalon.com